First, a large body of work looks at the impact of remittances at the macroeconomic and microeconomic level. This paper is related to several strands of the literature. Against this backdrop, this paper attempts to address the following questions: how elastic are remittances to changes in transaction costs? what are the factors or policy interventions that may help explain cross-country differences in the cost elasticity of remittances? Because formal remittances involve high fixed costs and hence are expensive to provide, low-income individuals refrain from remitting, or are incentivized to use cheaper informal alternatives ( Gibson, McKenzie and Rohorua, 2006 Yang, 2011). Considering fees, exchange rate margin and other costs, between 5 and 15 percent of remittances are “lost” due to high transaction costs, depending on the country and the amounts send home ( Ratha, 2021). It is accepted wisdom that individuals sending money home in many parts of the world, particularly sub-Saharan Africa, are paying a very high cost, which may dissuade further flows. 1 The strong resilience of remittances during the Covid-19 pandemic has brought back to the forefront the debate surrounding the stubbornly high transaction costs (see Kpodar et al., 2021). Despite the commitments from the international community to reduce the cost of remittances, and the inclusion of the 3 percent cost target in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), progress has been slow in recent years. However, a major stumbling block in sending money home is the high, some would argue excessive, transaction costs involved. Over half of it goes to people in rural areas, and about 75 percent is used to cover basics such as food and medical or school expenses, while the remaining is invested in assets or saved ( IFAD, 2021).īeing a major source of income for the poorest households, policy makers in advanced and developing countries are looking at avenues to encourage remittance flows to grow even further. According to World Bank data, remittances to low- and middle-income countries more than doubled during the past 15 years to reach US$550 billion in 2021. Migrants send part of their earnings to family members to provide them with basic subsistence, build and invest in the economy back home.

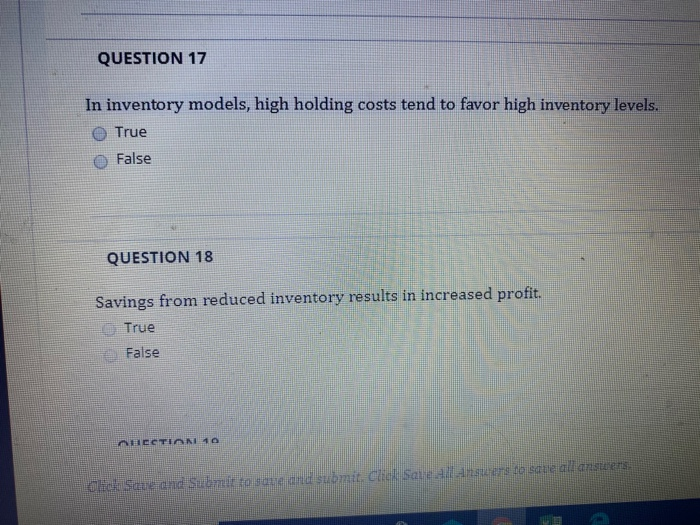

They are a key source of funding for developing countries. Supplementing the panel analysis, the use of micro data from the USA-Mexico corridor confirm that migrants facing higher transaction costs tend to remit less, and that this effect is less pronounced for skilled migrants and those that have access to a bank account. Similarly, remittance cost-adaptation factors such as enhanced transparency in remittance costs, improved financial literary and higher ICT development coincide with remittances being less sensitive to transaction costs. Among remittance cost-mitigation factors, higher competition in the remittance market, a deeper financial sector, and adequate correspondent banking relationships are associated with a lower elasticity of remittance to transaction costs. According to our estimates, reducing transaction costs to the Sustainable Development Goal target of 3 percent could generate an additional US$32bn in remittances, higher that the direct cost savings from lower transaction costs, thus suggesting an absolute elasticity greater than one. The findings suggest that cost reductions have a short-term positive impact on remittances, that dissipates beyond one quarter. It adds to the literature by systematically exploring the heterogeneity in the cost-elasticity of remittances along several country characteristics. Using a new quarterly panel database on remittances (71 countries over the period 2011Q1- 2020Q4), this paper investigates the elasticity of remittances to transaction costs in a high frequency and dynamic setting.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)